Die Antwoord (1) South Africa’s answer to Lady Gaga (2) recently released a promotional video for their new album Ten$ion that referenced iconic South African sculpture The Butcher Boys.

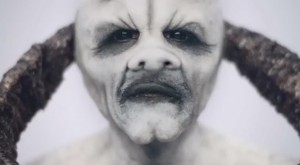

The video features a horned creature that was influenced by The Butcher Boys a plastic sculpture created by Jane Alexander and kept in the South African National Art Gallery. A still from the video shows the creature.

According to accounts in the press Jane Alexander, the artist who created the sculpture was unhappy with the use made of her work and retained a firm of attorneys. Die Antwoord immediately withdrew the video. The South African Art Times has an interesting account. Go and read it now.

Back? Then you’ll have read that zef rapper Ninja claims a friendly relationship with Alexander, that the horned creature in the video was made in “homage to one of our favourite SA icons”, his surprise at Alexander’s objection and the immediate withdrawal of the video. The action seems to be over.

But the reactions are not over, and they raise important legal questions to which there does not seem to be an easy answer.

Linda Stupart questions “whether we .. have the right to be all postmodernly pastiching this iconic image of Apartheid oppression”.

Emma Bedford, an art expert at Strauss & Co claims that “While referencing and sampling have become the order of the day across the arts, the rights of the artist to assert their authorship and contest the wholesale theft or corruption of their work must be able to be asserted.”

Kathryn Smith who lectures Visual Arts at Stellenbosch University commented “The fact is that Die Antwoord goes viral internationally and will reach more people than a local artwork could conceivably do, and will thereby profit from a video which clearly references this iconic work.

Mary Corrigal asserts that “in this copy-and-paste age of appropriation and pastiche, asserting originality or ownership over cultural property has to some degree become a futile, if not unnecessary activity, though cases of ownership are constantly being tested in courts all the time. It is not just artists or musicians who regurgitate and recycle material; almost everyone who spends anytime on the internet has repurposed imagery.”

There is a raging public debate in social media. Much of the debate has been characterised by mistaken claims that referencing an artwork is equivalent to copying or adapting it, the conflation of political and aesthetic claims with legal issues and the confusion of copyright with moral rights. Of course the law applies in a political context, and has unarticulated aesthetic preferences so that the issues necessarily affect each other. But the reason for confusion is more fundamental. Note how Stupart asks whether “we” have the right. I understand her to be making an entirely non legal argument, the “right” in question being a proxy term for whether the behaviour is appropriate. It is a symptom of our contemporary moral impoverishment that it is difficult to imagine couching the question in terms of virtue or even principle, instead cultural and political discourse must borrow its language from law. There is also no cultural institution which could have resolved the issue, and instead the artist turned to the legal system. Stupart is posing an important question and the rights language which she uses is the language of contemporary moral and political discourse which seems to be unable to rid itself of a confusing and confused reliance on legal tropes.

But the law doesn’t or at least shouldn’t exhaust the question of what art is or is not appropriate in South Africa in 2012. Whether particular artistic expression should be allowed because of freedom of expression is a political as well as legal debate, but even if an expression is legally permissible that does not mean that it is politically responsible or culturally appropriate. I haven’t seen anyone claim that when the law does prohibit particular expression that it follows that that expression is automatically immoral or ugly. The converse is also true, if the law permits particular artistic expression we can still argue about whether the artist should have done what he did, and we can boycott galleries and shops that show and sell the artwork and withhold our donations from those who support the artist, these actions form part of the same liberty as the freedom of the artist.

A debate about whether it was appropriate for Die Antwoord to draw on The Butcher Boys as they did, and whether it was appropriate for Jane Alexander to object, and to take legal action will be a better debate when it is clear what the legal questions are, and to what extent current South African law provides answers to those questions.

The first legal question is whether there was any infringement of an exclusive right set out in the 1978 Copyright Act. The artist, or persons to whom she cedes her copyright, is the only person who may authorize copies or adaptations of an artwork. The copyright holder has the exclusive right of authorizing the inclusion of the work in a cinematograohic film (that terms includes video clips). The artist also has a ‘moral right’ (actually a legal right referred to section 20 of the Copyright Act as a ‘moral right’ ) “to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work where such action is or would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author”. These rights are all subject to exceptions (3).

Section 20 goes on to state that an infringement of the section should be treated like an infringement of copyright. The moral right is not transferred with the copyright. Moral rights in copyright legislation originate not in the utilitarian scheme of Anglo-American copyright law from which South African copyright law is derived but in the French droit d’auteur tradition. In that tradition moral rights are routinely used by artists against subsequent copyright holders, pitting Mammon against the Muses.

How does the moral right overlap with the copyright rights? The moral right operates only when there is a change to the work. Simply copying the work cannot trigger the moral right because some modification is required as one of the essential elements of an infringement. How does the exclusive right to authorize adaptations intersect with moral rights?

Adaptation is defined in the Copyright Act: ‘ “adaptation”, in relation to – an artistic work, includes a transformation of the work in such a manner that the original or substantial features thereof remain recognizable.’ It is not clear from the Copyright Act whether what is required is a modification of the original sculpture or painting or whether modification of what would otherwise be a copy is an adaptation (4). Both the adaptation right and the moral right require modification of the work, not just re-use of some elements. The question is: is the second work a modification of the first work or does it merely incorporate some elements of it? Is the costume used in the Ten$ion trailer a modification of the sculpture or does it merely incorporate some elements of it?

Does the video infringe the copyright or moral rights of the author? The sculpture itself was not incorporated in the video, nor does the video show another sculpture copied from the statute. Instead Die Antwoord claim that elements of the video were inspired by the sculpture (5). It would require a close analysis of both sculpture and video to ascertain whether the video is an adaptation or just bears some similarities to the sculpture. One artwork can reference another without being an adaptation. Think of T S Eliot’s The WasteLand which contains numerous literary references without being an adaptation of any of them.

If the mask and costume used in the video is an adaptation the question that follows is whether it is authorized by an exception in copyright law.

Regular readers of this blog will recall posts on the Yada Yada parody of a Santam advert. In one of those posts I discussed the fair quotation provision in South African Copyright law.

“Section 12(3) states: ‘The copyright in a … work which is lawfully available to the public shall not be infringed by any quotation therefrom, including any quotation from articles in newspapers or periodicals that are in the form of summaries of any such work: Provided that the quotation shall be compatible with fair practice, that the extent thereof shall not exceed the extent justified by the purpose and that the source shall be mentioned, as well as the name of the author if it appears on the work.’ Fair practise is not defined although Professor Dean suggests that it should follow the four factor analysis of fair use in United States copyright law.”

But does the section 12(3) exception apply to artistic works. The way that the 1978 Copyright Act is structured is that each category of work such a literary works or artistic works has a different idiosyncratic list of exceptions. Some of those exceptions are created by reference to exceptions for other categories of works. It can be quite tricky to figure out which exception applies to which kind of work if you just read the Act. I tend to use the table setting what applies to what, you can find the table on page 15 of the Open Review of the South African Copyright Act.

Section 15 which sets out the exceptions that apply to artistic works states that s12(3) [the fair quotation exception] does not apply to artistic works.. So the fair quotation exception does not apply to artistic works.

Another possible exception is s12(1) ‘fair dealing’ which includes criticism or review. It is possible to make an argument that when one art work comments on or refers to another that this could constitute criticism. One merit of the argument is that it would allow a court to save the Copyright Act from a declaration of unconstitutionality. The Copyright Act is apartheid era legislation which must be tested against the Constitution. If the Act limits the rights in the Bill of Rights unjustifiably then it must be struck down.

Section 16(1) of the Bill of Rights sets out the right to freedom of expression and explicitly includes freedom of artistic creation. If the Copyright Act is interpreted so that it does not enable a court to balance the competing rights of the artist and the copyright holder (often not the same person) and the rights of others artists and the rights of the public the the Act violates the right to freedom of expression unconstitutionally, and should be struck down.

The moral rights provision was enacted in 1978 in the per-Constitutional era of South African law. It was enacted to comply with South Africa’s treaty obligations from the Berne Convention. The formulation of the right in the Copyright Act leaves a number of questions about the right unanswered. There have been no reported cases on moral rights in South Africa which could have offered guidance.

The moral right is obviously a limit on freedom of expression. The limitation would have to be justified. One factor in a justification’s analysis is the right to dignity in the Bill of Rights which could weigh in favour of the moral right. Case law from other jurisdictions suggests that to qualify for infringement of the right the issue is not that the use made of an artwork was made without permission, nor that it simply offends the artistic sensibilities of the artist e.g. dance remix of heavy metal song. Instead the use must really be fundamentally repugnant for example neo Nazis using artwork made by a Jewish artist. So where does the use by Die Antwoord fit? Was it a tribute to Jane Alexander’s work? Or was it “distortion”?

(1) For those unfamiliar with the Afrikaans language “Die Antwoord” means “The Answer”.

(2) Lady Gaga is not the question, the question is who has the most bizzare musicians in the world.

(3) The Copyright Act does not state in so many words that the exceptions to the exclusive rights of copyright set out in Chapter 1 apply to moral rights. Instead it states that infringements of the moral right must be treated as infringements of exclusive rights in terms of Chapter 2. Section 23 in Chapter 2 states that doing an act which the author has the exclusive right to authorize, as specified in Chapter 1, without authorization constitutes an infringement. Chapter 1 provides exceptional actions by which copyright “shall not be infringed. If a court were to rule that the exception do not apply to moral rights the result would be that it would be even harder to justify the way in which the moral rights provisions limits constitutionally protected expression, and therefore make it more likely for a court to find that the moral right section is contrary to the Bill of Rights and should be struck down

(4) One possible consequence of the legal uncertainty is that the mask could be regarded as an adaptation because it is not a transformation of the original physical sculpture. Therefore it would not be not infringing.

(5) It isn’t clear if there was a series of “copying” in which Die Antwoord modified digital images of The Butcher Boys in the physical process of constructing the mask. The Copyright Act defines copy as reproduce, and reproduction in turn ‘in relation to – an artistic work, includes a version produced by converting the work into a three dimensional form or, if it is in three dimensions, by converting it into a two-dimensional form’. If the facts supported it it would be possible to make the argument that the conversion of the three dimensional sculpture into a two dimensional image, and then the conversion of the image into a three dimensional mask and costume amount to copying. However the end result although similar is not the same and is therefore not a copy. For artistic works an adaptation is not by definition a copy.